Meeting, Guiding, and Orienting a Person Who is Blind or Low Vision

Family, friends, and professionals are often unsure of how to interact with and assist older people who are blind or low vision. They aren’t sure what individuals can see, what is considered standard courtesy, and what type of assistance older people who are blind or low vision may desire.

Know that the vision of one who is blind or low vision depends on their eye condition, day-to-day fluctuations, and factors such as poor lighting or glare. It is also beneficial to understand standard courtesy for meeting, guiding, and orienting people who are blind or low vision. The techniques are useful when interacting with an individual who is blind or low vision and when assisting them if help is requested.

Guiding Techniques

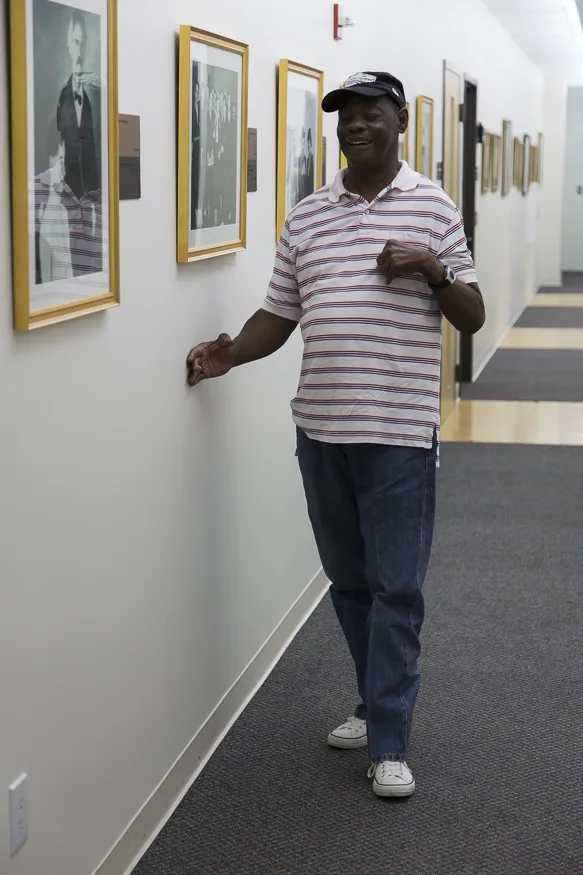

Demonstrating Human Guide Technique

Demonstrating Human Guide Technique

Identify yourself verbally when meeting someone who is blind or low vision. State their name so they know that you are talking to them and don’t walk away without telling them.

- When guiding, don’t try to push or pull. Let them take your arm just above the elbow.

- Speak directly to the person who is blind or low vision, not through another person.

- Speak naturally. There’s no need to raise your voice unless you have hearing loss. Check out our tip sheet on meeting someone with hearing and vision loss for more information.

- Give directions with details. Instead of saying, “The bench is over there,” say, “The bench is to your immediate right.”

- When visiting someone who is blind or low vision, don’t move things without asking; always put things back where you found them.

- Remember, the person who is blind or low vision is the best one to tell you how you can help. Just ask!

- Above all, treat a person who is blind or low vision with dignity and respect.

Trailing and Self-Protective Techniques

The trailing technique is useful when a person who is blind or low vision is in an unknown environment. It can help find a door or detect objects in front of a person. When trailing, the person should always use the back of the hand. A cautionary note: this technique will not help locate drop-offs such as stairs or with face-level objects. An adequately used cane can locate drop-offs.

The upper body technique involves positioning the forearm about 10 inches before the upper body with the palm out and fingers splayed. The lower body technique protects the lower body with one arm angled across the lower part of the body and the palm facing inward.

Upper body self-protective technique

Upper body self-protective technique

A person who is blind or low vision can learn to use non-visual information–other senses, such as hearing, touch, smell—to gather valuable clues. Sounds, such as the hum of an appliance, smells such as deodorizers, or touch, such as the feel of textures like carpet, can all help orient a person to the environment.

Orientation and Mobility Specialists

Your family member will likely also benefit from professional training to build confidence and independence in travel. Orientation and Mobility (O&M) Specialists provide this support, teaching practical skills that combine sensory awareness, protective techniques, and safe travel strategies for a variety of environments.

O&M Specialists provide services across the lifespan, teaching infants and children in pre-school and school programs and adults in various community-based and rehabilitation settings.

The Academy for Certification of Vision Rehabilitation and Education Professionals (ACVREP) offers certification for vision rehabilitation professionals, including O&M Specialists. A Certified Orientation and Mobility Specialist (COMS) must adhere to a professional Code of Ethics and demonstrate knowledge and teaching skills in the following areas:

- Sensory development, or maximizing senses to help one know where they are and where they want to go

- Using remaining senses in combination with self-protective techniques and human guide techniques to move safely through indoor and outdoor environments

- Using a cane and other devices to walk safely and efficiently

- Soliciting and/or declining assistance

- Finding destinations with strategies that include following directions and using landmarks and compass directions

- Techniques for crossing streets, such as analyzing and identifying intersections and traffic patterns

- Problem-solving skills to determine what to do if one is disoriented or lost or need to change the route

- Using public transportation and transit systems.

Amy Bovaird, Author of Mobility Matters: Stepping Out in Faith and Cane Confessions: The Lighter Side to Mobility

Amy Bovaird is a VisionAware Peer Advisor and author of Mobility Matters: Stepping Out in Faith and Cane Confessions: The Lighter Side to Mobility, her compelling memoirs that recount her life as an international teacher and traveler, her diagnosis of retinitis pigmentosa, and her triumph at learning to travel independently once again, using her long white cane.

Says Amy, “Mobility matters. It allows me to join the rest of society, follow my interests and passions, and reconnect with my love for traveling. I don’t have to stay at home fearing the dark anymore. I can live independently.”Learn more about ways to find emotional support for you – and your family members – after an eye condition diagnosis: