Art Appreciation and Hanging Framed Pictures if Blind or Low Vision

Painting, as well as other types of artwork, is more than just a visual experience — it can also be a rich sensory experience, an opportunity to express yourself, and a way to interact with people from all walks of life.

Suppose you are considering taking up painting as a hobby or resuming your prior artistic pursuits. In that case, you can draw inspiration from well-known artists with vision problems who persevered with their art. In particular, Claude Monet and Edgar Degas wrote extensively about the effects of declining vision on their lives and art.

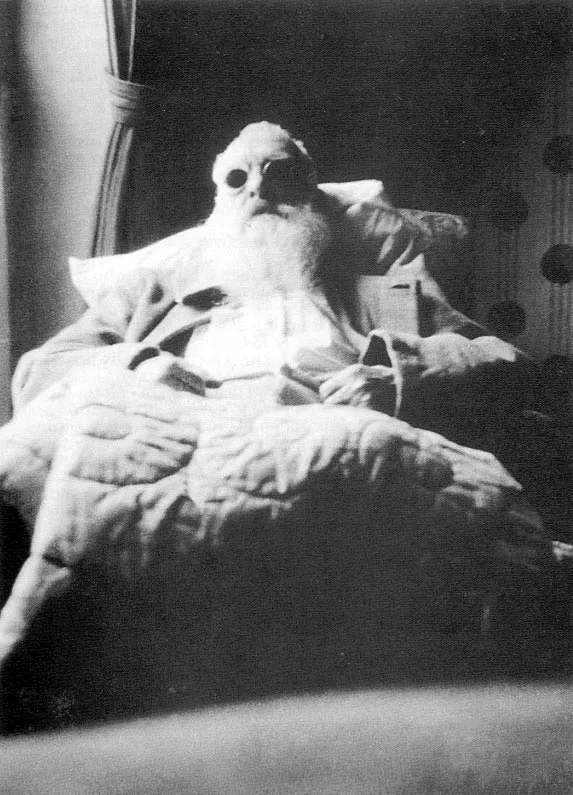

Monet laying in bed after his cataract operation wearing dark round glasses.

Monet laying in bed after his cataract operation wearing dark round glasses.

Claude-Oscar Monet (1840-1926)

Claude Monet was a leader of the French Impressionist movement. He is perhaps best known for his series of paintings inspired by the water lilies in his garden at Giverny in France.

Many researchers now agree that Monet painted in his distinctive style because he experienced the effects of cataracts throughout his later career, during which he produced some of his most characteristic work. He underwent two cataract surgeries in 1923, two years before his death at 86.

As Monet’s vision decreased, his color perception changed, and his palette shifted from the pastel floral hues of his early work to the darker browns and reds of his later career, best illustrated by two of his most famous paintings.

Monet painted The Water-Lily Pond in 1899 when he was 59:

Claude Monet’s ‘The Lily Pond,’ also known as ‘The Japanese Bridge,’ depicts a curved wooden bridge arching over a pond filled with water lilies. Soft green foliage and dappled reflections fill the scene, painted in loose, impressionistic brushstrokes. The image evokes a serene, dreamlike garden atmosphere.

Claude Monet’s ‘The Lily Pond,’ also known as ‘The Japanese Bridge,’ depicts a curved wooden bridge arching over a pond filled with water lilies. Soft green foliage and dappled reflections fill the scene, painted in loose, impressionistic brushstrokes. The image evokes a serene, dreamlike garden atmosphere.

In contrast, Monet painted the same scene in The Japanese Bridge between 1923-24, when the effects of his cataracts were most pronounced. His style had changed, but his artistry was intact, as illustrated in the following painting:

Claude Monet’s 1923–25 ‘The Japanese Bridge’ depicts a curved bridge over a pond, rendered in thick, vibrant brushstrokes of fiery reds, golds, and deep blues. The scene is abstracted, with the bridge and foliage blending into a rich tapestry of autumnal color and light.

Claude Monet’s 1923–25 ‘The Japanese Bridge’ depicts a curved bridge over a pond, rendered in thick, vibrant brushstrokes of fiery reds, golds, and deep blues. The scene is abstracted, with the bridge and foliage blending into a rich tapestry of autumnal color and light.

Edgar Degas (1834-1917)

Edgar Degas was a French painter, sculptor, and engraver. He is best known for his paintings of dancers, and he excelled in capturing their movement and artistry.

Degas’ vision problems began in 1870 at age 36, probably due to retinopathy or problems with his retina. He found it difficult to tolerate bright light, especially sunlight, and preferred to work indoors in more light-controlled environments, such as the opera and ballet stages he depicted in many of his paintings.

In 1874, at age 40, Degas also developed a loss of central vision, possibly from macular degeneration. His vision continued to deteriorate, and by 1891, at age 57, he could no longer read print. As his vision changed, however, Degas learned to adapt. He began working with pastels instead of oils (since pastels require less precision), and took up sculpture, printmaking, and photography.

To better understand how Degas’s vision changed, comparing his paintings is helpful.

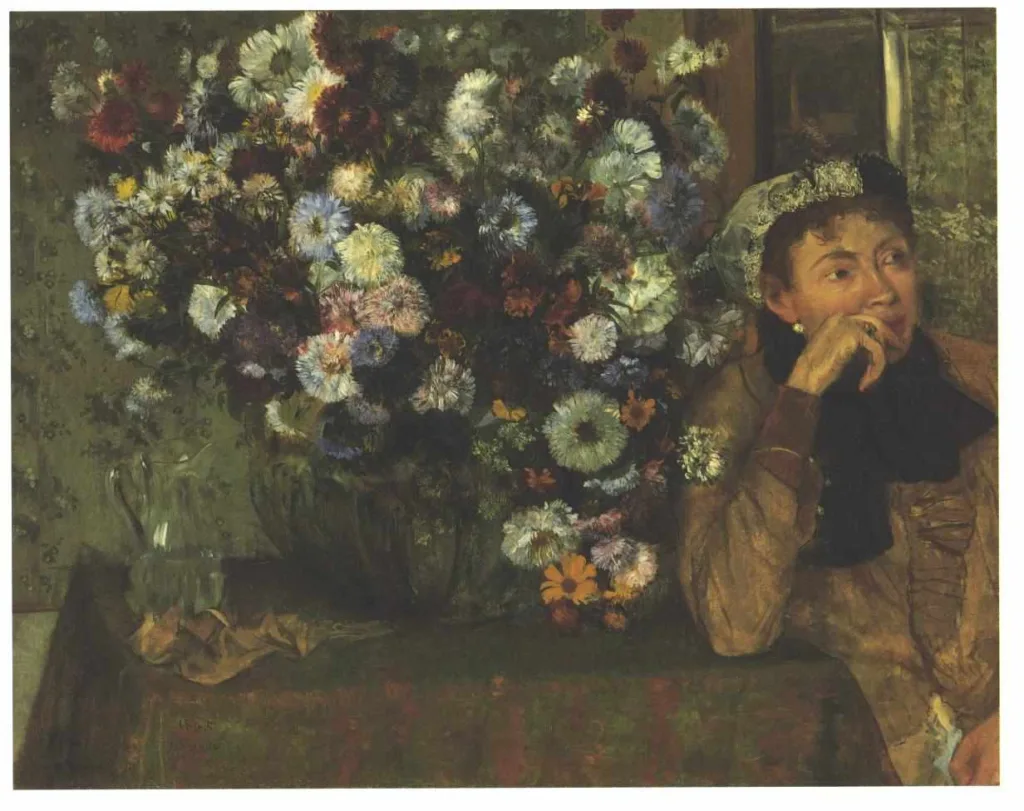

Degas painted A Woman with Chrysanthemums, which contains much fine detail, in 1865, when he was 31:

A Woman with Chrysanthemums

A Woman with Chrysanthemums

A woman seated beside a luminous vase of chrysanthemums and asters dominates the right margin of the canvas, while the floral arrangement takes center stage in rich, textured detail—she gazes dreamily to the right, partially obscuring her face with her hand, creating a quietly introspective mood.

In contrast, Degas painted Two Dancers, which contains broad brush strokes and very little fine detail, in the period between 1890-1898, when his vision problems were well advanced:

Edgar Degas’s ‘The Two Dancers’ depicts two ballerinas in orange bodices and pale tutus, standing backstage with hands on hips. Rendered in soft pastels, the scene captures their poised stance against a backdrop of warm and cool tones.

Edgar Degas’s ‘The Two Dancers’ depicts two ballerinas in orange bodices and pale tutus, standing backstage with hands on hips. Rendered in soft pastels, the scene captures their poised stance against a backdrop of warm and cool tones.

Rembrandt van Rijn (1606-1669)

Rembrandt van Rijn was a Dutch artist, generally considered one of the greatest painters and printmakers in European art history and the most important in Dutch history.

Several researchers believe that Rembrandt may have had stereo blindness (dissimilar visual images received by his left and right eyes), since many of his self-portraits show each of his eyes looking in a different direction, as in Self-Portrait as a Young Man:

Rembrandt Self Portrait as a Young Man

Rembrandt Self Portrait as a Young Man

This lack of binocular vision may have caused problems with Rembrandt’s depth perception – but it also may have helped his art by making Rembrandt exceptionally aware of light changes, shadows, and other details that helped him judge distances and depth and depict a realistic three-dimensional world on a flat canvas.

One of Rembrandt’s most famous paintings is The Night Watch (1642), known for its effective use of light, depth, shadow, and the perception of motion he created on the canvas:

Rembrandt The Night Watch

Georgia O’Keeffe (1887-1986)

Georgia O’Keeffe was an American artist known primarily for her abstract paintings of flowers, rocks, shells, animal bones, and landscapes.

By the early 1970s, when she was in her 80s, her eyesight began to decline due to macular degeneration. Then, she expanded her artistic interests and began working with clay and creating video projects.

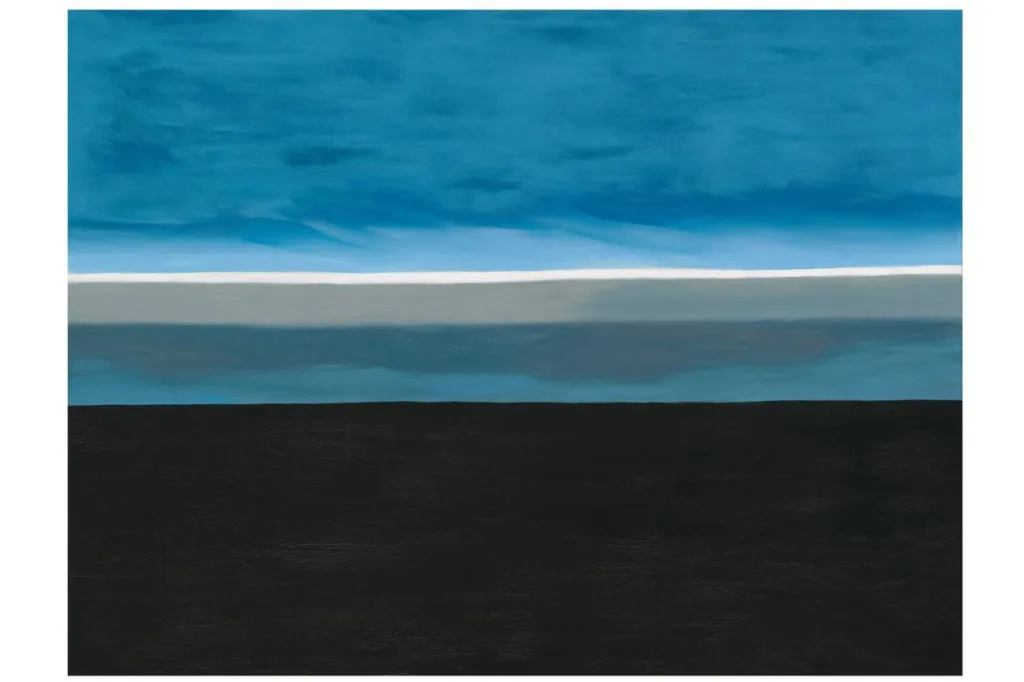

She completed The Beyond, her last unassisted work in oil, in 1972, at age 85:

Georgia O’Keeffe’s ‘The Beyond’ shows a sweeping horizon of deep blue sea meeting a pale sky, framed by soft, cloudlike shapes. Minimalist forms and gentle gradients evoke a sense of vast space and calm. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum.

Georgia O’Keeffe’s ‘The Beyond’ shows a sweeping horizon of deep blue sea meeting a pale sky, framed by soft, cloudlike shapes. Minimalist forms and gentle gradients evoke a sense of vast space and calm. Georgia O’Keeffe Museum.

O’Keeffe also continued to work unassisted in watercolor and charcoal until 1978 and in graphite until 1984, when she was 97.

Organizational Hints and Adaptations for Painting

Here are some everyday hints to help you organize your painting area and create adaptations for your art and painting projects:

- If you have low vision, a flexible-arm task lamp can direct light onto your work area. Some lamps also have built-in magnifiers.

- Make good use of natural light and position your easel or drawing board so that the sun is behind you and shines over your shoulder and onto your work.

- Consider a change of subject or style. For example, try landscapes instead of portraits or abstract painting instead of realism.

- If you have low vision, ask your eye doctor about low-vision optical devices, such as spectacle-mounted telescopes, that may help you see and study objects while keeping your hands free to paint. Some artists have had success using desktop or portable electronic video magnifiers.

- Label your supplies in large bold print made with a wide-tipped felt marker or a tactile marking in braille. For more ideas about labeling your art supplies, see Labeling and Marking.

There are several ways to ensure that your pictures and other wall decorations are level:

Hanging Framed Photos if you are Blind or Low Vision

There are several ways to ensure that your pictures and other wall decorations are level:

Use an Adapted Level

- You can use an audible level that emits different tones and beeps to indicate whether a picture (or any other household item) is level. It makes a high-pitched sound when the left side is higher, a lower-pitched sound when the right side is higher, and is silent when the picture is level.

- If you have low vision, you can try using a lighted level with lighted vials that allow work in dark and low-light environments.

Use Everyday Materials

- You can also use a homemade measure, such as a broom handle, yardstick, or piece of string, to ensure that your picture is hanging level on the wall.

- If you use string: Measure from the bottom corner on one side of the picture to the floor and then from the other bottom corner to the floor. To use the string technique, knot the string, attach it to one bottom corner with tape or to the wall with a pushpin, and measure the distance from the corner to the floor. Repeat this technique on the other side of the picture. When both measurements are the same, you will know the picture is level.

- If you use a broom or yardstick: Measure from the ceiling, since that may be the shorter distance. Measure from one top corner of the picture to the ceiling and then from the other top corner to the ceiling. When both measurements are the same, you will know the picture is level.

Additional Picture Hanging Tips and Adaptations

Here are some additional tips for hanging pictures.

- Place a small dab of toothpaste (preferably white) on the picture hanger wire. Position the picture on the wall and push on the hanger wire so that the dab of toothpaste transfers to, and remains on, the wall. This will mark the spot to hammer your nail or picture hanger.

- To hang a picture that requires multiple nails, lay a strip of masking tape along the back of the frame. Make holes in the tape to mark where you want the nails to go. Then pull the tape off and stick it to the wall. The holes in the masking tape will mark the spots to hammer your nails or picture hangers.

- Always hang heavier pictures or mirrors from wall studs that will support their weight. Use a stud finder that makes an audible sound (usually a beep) and lights up when it locates a wall stud.

- If you don’t have a stud finder, you can run an electric razor over the wall. The sound of the razor will change when it vibrates over the stud.

For additional work preparation and safety tips, see Home Repairs Safety and Preparation Checklist and Safety Tips and Techniques for Using a Hammer.