Retinitis Pigmentosa: What is it?

Retinitis pigmentosa (RP) is the most common of a large group of progressive retinal degenerations or dystrophies [i.e., degenerative disorders].

There is considerable overlap among the various types. It usually refers to a group of hereditary conditions involving one or several retina layers, causing progressive degeneration.

What Causes Retinitis Pigmentosa?

Retinitis pigmentosa is an inherited condition caused by mutations in genes important for rod and cone function. While many genes can cause RP, a single gene is responsible for each affected individual or family. Genetic testing can reveal which gene is responsible in a given individual.

Suppose you have been diagnosed with retinitis pigmentosa. In that case, you may wish to undergo genetic testing with the aid of a genetic counselor, who will also ask questions about your family history and family tree (called a “genetic pedigree”). Usually, this is managed by a retinal specialist, who may also enlist the help of “super-specialists.” A super-specialist is a physician with additional, highly specific training in a specialty area of medicine, and this case refers to a retinal dystrophy specialist.

Retinitis pigmentosa occurs in approximately 1 in 4,000 people in the United States. A related condition, Usher syndrome, includes retinitis pigmentosa accompanied by significant hearing loss from birth.

What Are the Symptoms and Signs of Retinitis Pigmentosa?

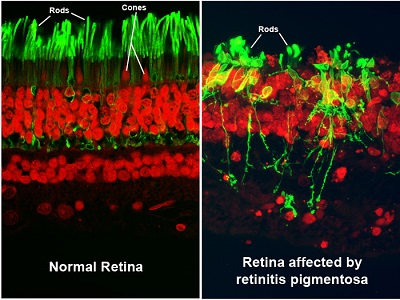

Since retinitis pigmentosa is a rod dystrophy, and rods are responsible for night vision, you will start to notice an increasing difficulty in night vision as the first symptom, followed by progressive constriction, or closing in, of the visual field [i.e., the total area an individual can see without moving the eyes from side to side]. This may progress to “tunnel vision,” considered legal blindness once the visual field is 20 degrees or less in the better-seeing eye. For comparison, a normal visual field is approximately 160 degrees.

Rarely, total blindness may eventually occur. In some younger patients, in addition to the visual findings, poor hearing or deafness may occur. Significant visual loss may not occur until later in life. Some patients retain useful central vision their entire life.

Symptoms of Retinitis Pigmentosa

Source Retinitis pigmentosa by Christian Hamel

Source Retinitis pigmentosa by Christian Hamel

Permission (Reusing this file)

© 2006 Hamel; licensee BioMed Central Ltd.

Some of the most common symptoms of retinitis pigmentosa include:

- Decreased vision at night or in low light

- Loss of side (peripheral) vision may cause the person to bump into tables, furniture, or doorways. The person with retinitis pigmentosa may not notice it, but it may be apparent to others.

- Loss of central vision (in advanced cases)

- Other indicators of retinitis pigmentosa are your family history (especially the possibility of retinitis pigmentosa appearing in other family members) and expressed visual concerns or complaints, such as being unable to see well at night or in low-light conditions.

The Comprehensive Eye Exam

- Primarily, retinitis pigmentosa is diagnosed by a comprehensive medical eye examination.

- During the examination, your ophthalmologist may observe characteristic bone spicule pigment deposits while looking at the back layers of your eye with an ophthalmoscope. This instrument allows your doctor to examine your retina by shining a beam of light through your pupil.

- A similar pattern appears in certain unrelated infectious and inflammatory conditions, which must be ruled out if suspected.

Visual Field Testing

- Visual field testing can determine how much peripheral (side) vision you have and how much surrounding area you can see, and will locate defects in the peripheral visual field related to the damage from retinitis pigmentosa.

- Your eye examination will include visual field testing via a “kinetic” or non-computerized visual field test, such as the Goldmann Perimeter Exam (the recommended field test for retinitis pigmentosa), or a computerized visual field test, such as the Humphrey Field Analyzer or the Octopus.

- The Goldmann Perimeter Exam (pictured below) resembles a large white bowl. One eye is covered while the other remains stationary and focused straight ahead. The doctor will move a stimulus (a light) from beyond the edge of your visual field into your visual field. The location at which you first see the stimulus will indicate the outer perimeter of your visual field. The doctor will analyze your exam responses to map your visual fields precisely.

The Goldmann Perimeter Exam

The Humphrey Field Analyzer (pictured below) also resembles a large bowl. One eye is covered with a patch while the other remains stationary and focused straight ahead. White lights of varying sizes and intensities will flash at different locations around the bowl. You will press a button whenever you see a flashing light, recording which lights you see and which you do not creates a visual field map.

The Humphrey Field Analyzer

The Octopus is a newer visual field machine that can test your visual field either by kinetic perimetry (by moving the light until you see it, similar to the Goldmann) or by static perimetry (by flashing the light in a particular location and changing the size and intensity until you see it, similar to the Humphrey). Over time, the visual field may reduce to a small central island of vision, causing “tunnel vision.” The final progression may be the complete loss of vision. Complete blindness is rare.

Electrophysiological Testing

- The ophthalmologist does diagnostic testing, often by referral to a university ophthalmology department, since many private offices don’t have this equipment. However, electrophysiology equipment is becoming more prevalent.

- The electroretinogram (ERG) measures your responses to light flashes via electrodes placed either on the surface of your eye, inside your eyelid, or on your skin. It is a painless test.

- The ERG shows how well your rods and cones are functioning. It will usually make the diagnosis in conjunction with the visual field and eye exam.

Genetic Testing

There are over 100 genes known to cause RP. Genetic testing is recommended, and it can usually identify the cause of disease in up to two-thirds of patients. Identifying the causative gene is valuable for several reasons:

- There are several clinical trials for RP for gene therapy and other treatments. Many of these clinical trials only enroll patients with specific genetic causes of RP. Therefore, genetic testing may help you determine if you are eligible for clinical trials now or in the future.

- Identifying the causative gene will also reveal the mode of inheritance (i.e., how the disease gets inherited from one generation to the next).

- Modes of inheritance include autosomal dominant, autosomal recessive, X-linked, and mitochondrial. Your family history will give your doctor a good clue to the mode of inheritance, but often, it’s not conclusive without genetic testing. The mode of inheritance determines how likely it is for different relatives (like children or siblings) to be affected by the same condition. Therefore, genetic testing may help you determine the risk to your family members.

- Most genetic causes of RP cause only RP, which is called non-syndromic RP. However, some genes cause RP plus other diseases, like hearing loss or kidney disease, and these cases are called syndromic RP. Genetic testing may reveal that you have a gene that typically causes syndromic RP and may be at risk for developing other diseases. In this case, your primary care doctor may be alerted to screen you for these other conditions.

Important to Make a Diagnosis

It is important to make a diagnosis so that the patient and family can be counseled as to the status of the disease, when driving might have to be

discontinued, and what low vision interventions and low vision devices (in the case of more advanced disease) might be available to allow maximum

use of the patient’s visual potential. Furthermore, a subset of patients will be eligible for clinical trials and can be counseled regarding the different

options available and where the trials are being conducted.

How Retinitis Pigmentosa Became a Gift

by Maribel Steele

As a writer, author, and speaker, I delight in connecting with others by sharing our personal stories. I feel blessed to be the mother of four healthy children, an aromatherapist and masseur, and I enjoy a variety of interests: writing, singing, gardening, learning about art history, and traveling.

My Diagnosis

My family emigrated to Australia from England when I was a young child. I was diagnosed with Retinitis Pigmentosa (RP), a degenerative eye condition during my teens, that caught us completely off guard.

Over a period of two years, my sight mysteriously began to fade. At first, it was easier to ignore the blurring of words on the classroom blackboard, passing it off as just another phase of adolescence. I was also painfully shy about the thought of being ‘different’ to the girls at school, so I kept quiet about needing to wear glasses.

In my parents’ eagerness to glean any insight into my clumsiness at home, walking into a door or spilling a glass, they often peered around corners to see how I managed visual tasks. If they asked me direct questions about what I could see, it annoyed me that there might be anything different to report since the last time they asked. My eyes were still a clear blue, seeing well on bright sunny days and not so well on overcast ones. I looked and felt normal in every other way. But the truth lurking behind my eyes was a different story. Within the thin layers of my retinas, cells were slowly reducing their ability to transmit visual signals to the brain.

As a shy adolescent, I feared being different from my peers and felt caught between two worlds. I couldn’t see myself as being blind and the label of “disabled” annoyed me deeply. It was like carrying a new passport with RP stamped across my character, barring my entry into my own future. Defiance rose within my mind and heart. I had a serious choice to make. I could either drown in self-pity and let go of my dreams, or I could see the diagnosis as an obstacle to overcome in reaching my goals.

Accepting RP

RP has given me a different perspective on life. My life is certainly different but not necessarily worse due to this so-called “disability.” I eventually made friends with RP by accepting that my eye condition is just one aspect of who I am. There is so much more to my life as a mother, wife, friend, writer, gardener, traveler, mentor and educator.

While seeking practical adaptations for my home and writing studio, I found self-acceptance and kind support from others, and I gradually learned that there are many methods for managing the challenges of sight loss. Along the way, I have attained many skills.

Careers

I eventually stepped into two new careers – motherhood and aromatherapy. Being a mother posed incredible challenges. My children taught me the true meaning of unconditional love as they guided and helped me in daily activities and were happy, even competitive, to be ‘mummy’s eyes.’ While my children were keen to help, I felt conveniently excused from having to face what I thought was the stigma of the white cane or mobility training. The stroller worked beautifully to barge my way through shopping centers with my keen young driver in the seat calling out directions!

Becoming an aromatherapist was a deeply satisfying accomplishment. Two years of training, two years of determination to obtain my professional certificates, two bright red seals stamped on cream paper next to my name – my new personal passport had finally arrived. My massage practice brought clients anxious to seek healing and relieve stress and physical ailments. Intuition guided my hands to troubled areas, and I learned about the importance of trust and the sharing of our stories through the ailments of our bodies. Yet, I still struggled with feelings of inadequacy because of my visual impairment.

Embracing Mobility

It wasn’t until I came face to face with the reality that I couldn’t keep bluffing my way around my local community that I took the bold step forward to apply for a guide dog. Within ten weeks, I was training with a lively four-legged companion. Nev brought me the gift of independent mobility, and as we stepped out together, my golden boy pranced with grace and dignity. I used to be afraid of showing any sign of my visual impairment, yet Nev and I often received much praise and admiration when we worked as a team. As my new motto became “have dog, will travel,” I gave presentations around Melbourne (Australia) to interested groups and training organizations.

My dear companion went to the Great Kennel in the sky, but his legacy lingers. I can now use a white cane and feel proud to have retained my independence by claiming the magic it brings when I travel, locally and overseas.

Gift of RP

As I see it, the gift of RP is that it allows me to be a beacon of hope to those who fear losing their sight. This was not who I imagined myself to be as a teenager. However, in my more mature years, I am extremely grateful to be seen as a ray of hope for anyone who needs that initial light of encouragement. For me, RP is the reason why I can help my community embrace having low vision as a part of life, not as a stigma to be ashamed of.

If you are new to RP, my most valuable suggestion is to encourage you to reach out to those who are on the journey, who understand the challenges, and who can share valuable insights as you tread and explore the new territory. With a willing heart and a practical approach to adaptation, you can discover the “gift” of RP , too.

You don’t have to change who you are, but you may need to modify your approach to make daily-life tasks achievable with less sight. APH VisionAware has a great deal of information about living with vision loss that you may want to check out. During RP awareness month, this may be the perfect time to start moving forward again towards your big picture goals to grow RP strong!

What Is the Treatment for Retinitis Pigmentosa?

Currently, there is no specific treatment for retinitis pigmentosa (RP). In the past, there were reports that a supplement of 15,000 I.U. of Vitamin A and fish oil supplements might be of some benefit.

However, the research group at the Mass Eye and Ear Institute, where the Vitamin A study was initially published, recently reported that Vitamin A does not make a difference in slowing down RP. The original patient data was reanalyzed using some new information published about electroretinography, and there was no difference in disease progression with or without Vitamin A.

There is some evidence to support the use of DHA and lutein, which may have a modest effect on slowing disease progression in RP.

Other lifestyle modifications that may help slow RP include protecting your eyes from ultraviolet light with sunglasses and hats when outside, refraining from smoking cigarettes, and getting cardiovascular exercise.

Low Vision Options

Low vision aids and occupational therapy can help you maximize the use of the vision you have. You should consider having comprehensive low-vision examination – performed by an ophthalmologist or optometrist specializing in low vision. They can evaluate you with various low vision aids and make recommendations. They often have low vision therapists in-house who can help you with strategies to adapt to constricted visual fields and blind spots.

For example, there are visual field-expanding glasses that use prisms. These have been developed for people with reduced peripheral vision. These special prism glasses can help you become more aware of your missing visual fields, making navigation and reading easier. They do not restore “normal” vision, but they have proven helpful for many everyday activities and specific mobility and travel functions. You may require specialized training from a certified low-vision therapist to use these glasses safely and productively.

Reverse telescopes can also be helpful if your field of vision is less than 10 degrees. These telescopes reduce the image to fit within your field of vision and require a visual acuity of 20/80 or better. You will need training in orientation and mobility to properly use these devices.

Cataracts and Cataract Surgery

Individuals with RP may also develop cataracts. Cataracts may be removed, as in other persons with cataracts, usually using an intraocular lens.

Macular Edema

Fluid in the center of your retina, or macular edema, is a common complication of RP that may reduce your central vision and can be treated by your ophthalmologist with eye drops or pills, or less commonly with injections.

Mental Health

Loss of vision is associated with anxiety and depression, and the mental health burden of RP should not be ignored. If you are experiencing anxiety or depression, it is important to reach out to your primary care doctor or ophthalmologist for a referral to a mental health professional. Mental well-being contributes to both your overall health as well as your ability to optimize your use of the vision you have.

Is There a Cure for Retinitis Pigmentosa?

Although there is not yet a cure, there is much retinitis pigmentosa research being carried out by universities and others in the United States and worldwide. Several clinical trials for RP are enrolling patients with particular genetic causes of RP or particular clinical features. To find out more about current clinical trials, ask your retina specialist or visit https://www.fightingblindness.org/clinical-trial-pipeline.

- Ask your eye doctor about low vision services and other vision rehabilitation services that can help you with everyday living.

- You can also read APH ConnectCenter personal story blogs about people coping successfully and living well with various eye diseases and disorders, including retinitis pigmentosa.

Portions of this article were published originally at http://www.medicinenet.com/retinitis_pigmentosa/article.htm.

Retinitis Pigmentosa in Children

Before discussing the visual symptoms of retinitis pigmentosa, it is important to understand the emotional impact of RP. Your child may be a teenager, already in a turbulent season of life, when they hear, “You are losing your vision and may go blind.” Encourage your child to identify all feelings instead of suppressing them, connect with other teens or adults with RP, and utilize professional counseling. There is life beyond vision loss, though it may take much grieving (occurring all over again when vision noticeably deteriorates) and time before the entire family recognizes it.

RP typically manifests with poor vision in dimly lit environments, termed “night blindness.” Traveling by car, bike, or foot, performing tasks, and recognizing people or objects becomes increasingly complex in dim light.

Orientation and mobility training becomes necessary to navigate safely using a cane and public transportation. The use of an infrared night scope may further aid evening travel. Additionally, a well-lit room and additional use of task lighting (lamps or other lights) will be helpful for the individual to read, obtain details, and utilize vision to participate in activities.

Progressive Peripheral Field Loss

RP typically advances to include progressive peripheral field loss. An individual with loss of peripheral vision has some degree of “tunnel vision,” making it difficult to gather comprehensive visual information in an environment. They will benefit from learning visual efficiency skills such as scanning an environment in an organized manner and possibly utilizing a reverse telescope to minimize the appearance of an image to see its entirety within the remaining field of vision. Additionally, the individual is likely to bump into side-lying and low-lying obstacles; they should utilize orientation and mobility skills, such as using a cane, to avoid obstacles. As RP progresses, sharp visual acuity, central vision, and color vision may deteriorate, possibly resulting in total blindness.

Loss of Sharp Visual Acuity

Loss of sharp visual acuity makes it difficult to recognize faces and facial expressions, access information from a classroom board or wall, view a speaker or performance, read print, and perform visual tasks of fine detail, such as threading a needle. To best use remaining vision, your child can be taught to increase the contrast of the environment, increase the contrast of print by using a CCTV or screen-magnification software, and increase task lighting. Several wearable digital low-vision aids are also available to optimize vision and improve magnification, contrast, and other features. Furthermore, for lectures and similar activities, your teen should select seating for optimal viewing, with good lighting and possibly closer to the front, depending on what needs to be viewed.

Loss of Central and Peripheral Vision

If your child loses central vision and peripheral vision, they must learn to complete tasks without the use of vision. Your child may be taught braille, screen-reading software to use the computer, and techniques for performing life skills and academic tasks from the teacher of students with visual impairments and orientation and mobility specialist. Better yet, your child should begin learning the aforementioned accommodations in preparation for complete loss of sight.

Sunlight and Glare

Throughout the progression of RP, it is common for bright sunlight and glare to cause significant discomfort and inability to see (this is known as a “white out”). Your child may benefit from specialized sunglasses (amber-tinted lenses), the use of a brimmed hat outdoors, and shutting blinds indoors if glare is present.

Needed Assessments

Your child’s teacher of students with visual impairments (sometimes known as a teacher of the visually impaired (TVI) should perform a functional vision assessment to determine how your child uses their vision in everyday life and a learning media assessment to determine which senses your child primarily uses to get information from the environment. These assessments and an orientation and mobility assessment conducted by a mobility specialist will give the team information needed to make specific recommendations for your child to access learning material and their environment. Often, these assessments are arranged by the school in many public school districts.

Portions of information on the page published originally at www.medicinenet.com/retinitis_pigmentosa/article.htm

Page content by Frank J. Weinstock, MD and edited and updated in 2024 by Abigal Fahim, MD