Floaters, Retinal Tears, and Retinal Detachments

By Mrinali Patel Gupta, M.D.

What Are Floaters?

As their name implies, floaters are usually small, black shapes that look like spots, squiggles, or threads and “float about” in one’s vision. They generally move as the eyes move and are most noticeable against a plain bright background, such as a white or light-colored wall.

What Causes Floaters?

Several conditions and changes within the eye can cause floaters. These are the most common:

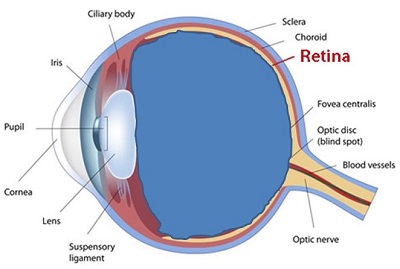

- Changes in the vitreous: The inside of the back part of the eye is filled with a jelly-like substance called vitreous. The vitreous is attached to the retina, which is the thin, light-sensitive tissue that lines the inside surface of the eye. Much like the film of a camera, cells in the retina convert incoming light into electrical impulses. The optic nerve carries these electrical impulses to the brain, which finally interprets them as visual images.

- As individual ages, the jelly-like vitreous becomes more liquefied, and areas of the vitreous can condense and acquire a “stringy” consistency. These strings or strands of vitreous can be perceived as floaters.

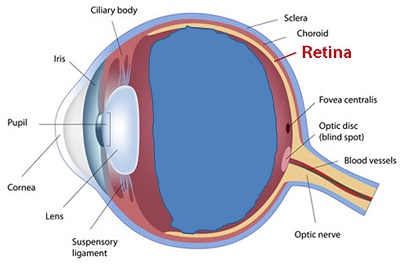

- Posterior vitreous detachment (PVD): As the vitreous liquefies, it also shrinks and pulls away from the retina. This process is called a posterior vitreous detachment, or PVD. Many people develop posterior vitreous detachments and never experience symptoms, whereas others may notice new floaters. In general, a vitreous detachment is not considered an ocular emergency.

The vitreous: A side view of the eye with the vitreous gel (in blue)

filling the inside of the back part of the eye and attached to the retina.

Source: Courtesy Mrinali Patel Gupta, M.D.,

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York

A posterior vitreous detachment (PVD): the vitreous gel (in blue)

shrinking and pulling away (detaching) from the retina.

Source: Courtesy Mrinali Patel Gupta, M.D.,

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York

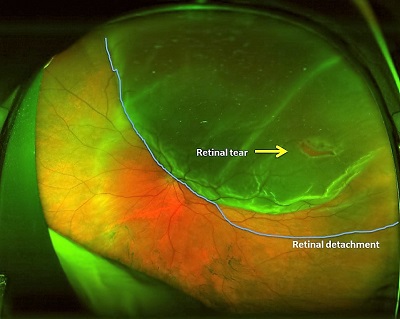

- Retinal tear or detachment: In some cases, as the vitreous is peeling away from the retina and detaching, it can pull so hard in areas of firm attachment that it tears the retina. Therefore, any person with a PVD should have a careful retinal exam to rule out an associated tear. As the retina tears, a retinal vessel may be torn or damaged, leaking blood into the vitreous. This blood called a vitreous hemorrhage, may also produce floaters. (See the photographs below in retinal tear and retinal detachment treatments to illustrate these processes.)

A tear in the retina is of great concern because it can extend and allow fluid to enter through the tear and separate the retina from the underlying tissue. To picture how this happens, imagine a rip in the wallpaper in the bathroom. That is like a retinal tear. If the rip is not repaired, steam from the bathroom shower can get behind the tear; eventually, the entire sheet of wallpaper may peel and fall off. A similar process occurs when a tear is untreated; the retina comes off or detaches.

Retinal tears often lead to retinal detachment. While retinal tears usually do not cause vision loss and can be repaired effectively through a non-incisional [i.e., no surgical cuts involved] laser or cold therapy (cryotherapy) procedure in the office without anesthesia, retinal detachments almost always cause vision loss (sometimes, severe vision loss or blindness) and usually involve incisional surgical repairs in an operating room. Therefore, it is critical to be evaluated promptly because diagnosing and treating a retinal tear before it results in a retinal detachment can be vision-saving.

Anyone can develop a retinal tear and detachment. Still, they are more likely to occur in persons who are nearsighted, older, have recently undergone cataract surgery, or have sustained eye trauma.

- Vitreous hemorrhage: In addition to retinal tears, other conditions that result in bleeding into the vitreous, such as proliferative diabetic retinopathy, can produce floaters and decreased vision.

- Inflammation: Less commonly, some inflammatory eye conditions, called uveitis, can lead to floaters.

Rocky’s Story: The Creation of the Frogtown Low Vision Support Group

Paul (Rocky) and Jan Rachow are the founders and facilitators of the Frogtown Low Vision Support Group. Rocky and Jan founded their support group after Rocky’s three retinal detachment surgeries.

Says Rocky, “There is no greater reward than watching someone come to our meetings with their head down and then, within a couple of months, watching their head held high with a smile on their face and a new appreciation of life.”

Learn more about ways to find emotional support for you – and your family members – after a diagnosis of blindness or low vision:

What Should You Do If You Notice Floaters?

Anyone who notices new floaters should undergo a dilated eye examination by an ophthalmologist. The ophthalmologist may use a Q-tip or small instrument to push gently on the eye to look at the far edges of the retina not visible through a routine examination.

Any patient with a prior history of floaters who notices a new shower of floaters, flashing lights, or a curtain or shade “coming down over one eye” should undergo a prompt eye examination. These may be signs of a retinal tear or retinal detachment.

Retinal tears often lead to retinal detachment. While retinal tears usually do not cause vision loss and can be repaired effectively through a non-incisional [i.e., no surgical cuts involved] laser or cold therapy (cryotherapy) procedure in the office without anesthesia, retinal detachments almost always cause vision loss (sometimes, severe vision loss or blindness) and usually involve incisional surgical repairs in an operating room. Therefore, it is critical to be evaluated promptly because diagnosing and treating a retinal tear before it results in a retinal detachment can be vision-saving.

How Are Floaters Treated?

- In all cases, the underlying cause of the floaters should be treated. The underlying cause of inflammation or bleeding should be identified and treated accordingly.

- If the floaters are due to changes in the vitreous or to posterior vitreous detachment, no intervention is necessary. A dilated eye examination should be performed to rule out an associated tear or detachment.

- In addition, many eye doctors may perform a follow-up exam in several weeks to confirm that a new tear or break has not developed in the retina. Over time, the floaters may decrease, and in many cases, the brain learns to ignore these floaters.

- The only effective way to remove floaters from the vitreous or posterior vitreous detachment is the surgically remove them. In rare cases, a vitrectomy (explained below) can be considered if floaters are causing significant visual symptoms. However, it is important to weigh the risks versus benefits of such a procedure.

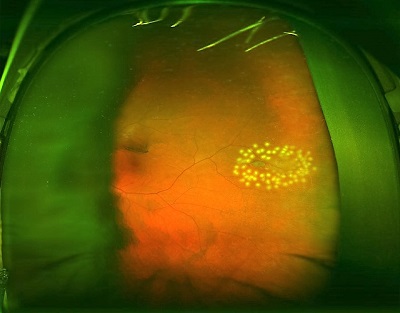

How Are Retinal Tears Treated?

- Cryotherapy (cold therapy) or laser therapy to seal the tears: The cryotherapy probe is placed on the outside surface of the eye, directly over the area of the retinal tear. In laser therapy, a laser is directed into the eye and focused on the retinal tear area.

- This treatment creates a scar around the tear to “spot weld” the retina to the eye wall surrounding the tear.

- Though these treatments are highly effective in preventing retinal detachment, there is still a risk of retinal detachment from the tear since fluid can collect under the retina through the tear, resulting in a retinal detachment. Therefore, patients should seek evaluation if there are any significant increases in the symptoms noted above.

A retinal tear before treatment.

Source: Courtesy Mrinali Patel Gupta, M.D.,

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York

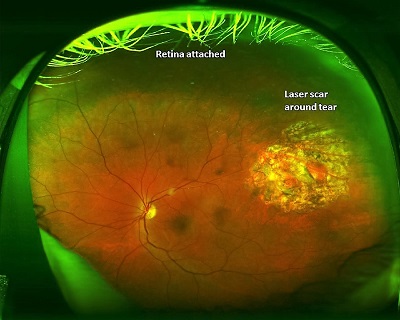

A retinal tear after laser treatment.

Source: Courtesy Mrinali Patel Gupta, M.D.,

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York

How Are Retinal Detachments Treated?

Retinal detachments can be repaired in one of several ways, depending upon the specific nature of the retinal detachment, other ocular findings, and patient preferences:

1. Cryotherapy or laser therapy to seal any breaks, along with pneumatic retinopexy

- Pneumatic retinopexy involves air injection or a gas bubble into the back of the eye. The bubble expands and seals the tear and the surrounding retina to prevent additional fluid from collecting under the retina. The fluid already present under the retina is slowly pumped out by cells in the retina, allowing the retina to reattach. The laser or cryotherapy seals the break, as described above.

- Based on the location of the retinal tear, the patient may have to maintain his or her head in a certain position to keep the bubble in the right location—for example, face-down positioning or sleeping on one side or the other. Patients with a gas bubble in the eye should not fly or dive since pressure changes in either situation can result in gas expansion and endanger the eye.

- Over several weeks, the gas bubble is replaced gradually by fluid created by the eye.

- This procedure is performed in the office setting, with topical anesthesia (drops or gels applied on the eye) or local anesthesia (anesthetic injected near or around the eye).

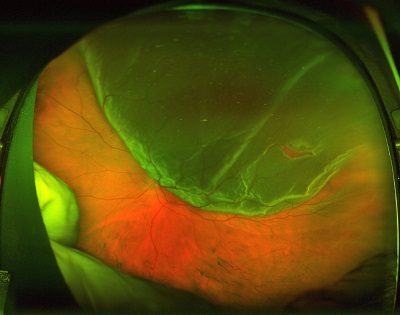

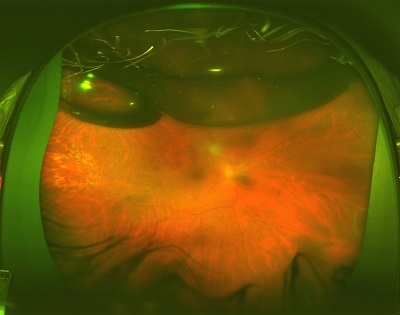

A retinal tear and retinal detachment before treatment.

Source: Courtesy Mrinali Patel Gupta, M.D.,

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York

After treatment with pars plana vitrectomy surgery, the above retinal tear and retinal detachment. The retina

is reattached, and there is a laser scar around the tear.

Source: Courtesy Mrinali Patel Gupta, M.D.,

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York

2. Scleral buckle surgery

- In scleral buckle surgery, a buckle (silicone sponge, rubber, or semi-hard plastic) is sewn to the sclera (the coating of fibrous tissue that covers the white part of the eye) to indent it and relieve traction or pulling from the vitreous on the retina.

- This surgery is performed outside the eye, although some surgeons may insert a needle into the eye under the retinal detachment to drain the fluid under the retina. The buckle remains in place after the conclusion of the surgery.

3. Pars plana vitrectomy surgery

- In vitrectomy, the vitreous is removed to relieve traction or pulling from the vitreous on the retina. All retinal breaks are identified, and traction from the vitreous is removed from the breaks in particular. The fluid under the retina is drained through one of the breaks, and a laser is applied to seal the breaks.

- A gas bubble is placed to seal the break and help the retina stay attached while the eye heals. As mentioned above, the gas bubble will require head positioning and prevent the ability to travel by airplane or to high altitudes. Over time, the gas will reabsorb on its own. Sometimes, an oil bubble may be placed instead of a gas bubble. Oil requires a second surgery in the future for removal.

A retinal detachment before treatment.

Source: Courtesy Mrinali Patel Gupta, M.D.,

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York

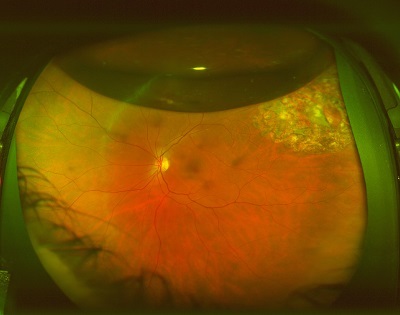

The above retinal detachment after treatment with

pars plana vitrectomy surgery and gas bubble.

Source: Courtesy Mrinali Patel Gupta, M.D.,

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York

The retina is now reattached after the gas bubble is gone.

Source: Courtesy Mrinali Patel Gupta, M.D.,

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York

4. Some cases of retinal detachment may require both vitrectomy and scleral buckle surgery.

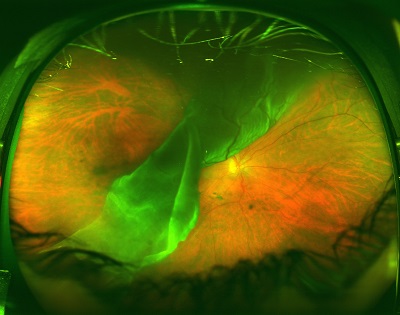

A giant retinal tear with retinal detachment before treatment.

Source: Courtesy Mrinali Patel Gupta, M.D.,

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York

The above giant retinal tear with retinal detachment after

repair with a scleral buckle and pars plana vitrectomy

with the placement of a gas bubble.

Source: Courtesy Mrinali Patel Gupta, M.D.,

Weill Cornell Medical College, New York

More About Surgery

- Both vitrectomy and scleral buckle surgery are performed in the operating room under anesthesia. Many cases can be performed with monitored anesthesia care, in which the patient is not put fully to sleep but is made comfortable with mild anesthesia.

- A local anesthetic is often administered around the eye to reduce discomfort and prevent eye movement during surgery. In some cases, general anesthesia may be required.

- Although prompt and appropriate intervention has a high success rate in repairing the retinal detachment (i.e., reattaching the retina), some cases will not achieve reattachment with a single surgery and may require additional interventions or surgeries.

- Even when the retina is successfully reattached, the subsequent visual outcome depends on several factors, including whether or not the macula was involved in the detachment and how long the detachment was present before repair.